(trailer)

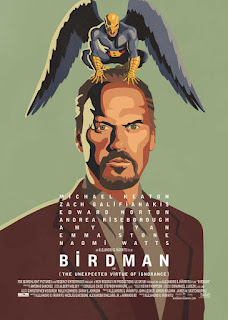

So I lied a little. I said this was “perhaps the best Batman movie.” And, by every definition, this is not a Batman movie. It does have Michael Keaton, perhaps the best Batman; Edward Norton, a former Bruce Banner; and Emma Stone, Sony’s new Gwen Stacy, along with at least one explosion-filled set piece, so perhaps I wasn’t too far off the mark.But I suppose calling Birdman a superhero movie comes with its own connotations. This isn’t a “stop the baddie” sort of movie (unless you count Edward Norton or Lindsay Duncan’s characters). It’s more of a long meditation on depression and obscurity. Michael Keaton’s Riggan Thomson had once starred in a series of superhero films for the character Birdman, though after declining an offer for Birdman 4, his life falls apart. He attempts to put it all back together by writing, directing, and starring in a Broadway adaptation of Raymond Carter’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, and the movie is about those final days before opening night, as characters need to be recast, familial relationships need to be mended, and psychoses need to be dealt with.

To be even more specific, Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) is about Riggan Thomson, and every character around him is some facet of his personality. His daughter is his fear of his own mundanity (multiple scenes with her involve a prop that represents just how short humanity’s time on Earth has truly been), his producer/lawyer/best friend (played by Zach Galfianakis) is his more realistic side, Edward Norton plays the rock-star-like persona he wishes he had, and so on. Amidst all of this, there’s also the Birdman persona itself, still haunting Thomson, jabbing at him throughout the movie with doses of self-doubt.

Talking about the structure of Birdman is difficult. The most-talked about feature of the movie is how much of it appears to be shot in one take, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope style, making it appear like its own theatre production, and as the most talked about feature, it tends to drown out the other elements, like how each scene is generally only two people, never really involving more of the ensemble outside of very special moments. This means that, despite the movie’s large ensemble cast, the movie still feels introspective, again, focusing on the character of Riggan Thomson.

What I find interesting is the people that call this movie pretentious. Maybe Birdman is too pretentious for its own good, maybe it isn’t. I certainly don’t think it is (I wouldn’t have written about it if I had), but even if it is, when stripped from perceived symbolism, it’s still the story of a man desperately clawing at whatever influence he has left, the story of low points and only the vaguest promise of things getting better in the end.

-F

Next: Oranges and tigers and emeralds, oh my!